Ladies and gents… (drum roll), the English version is here. Enjoy!

Day 1.

The blessings of individual travel

It’s not every year that we are gifted with additional time. But a leap year calls for a leap of faith, and so, I leap out of the plane from Munich to Málaga in southern Spain avid for sun, lush foliage, and the priceless nuggets of culture that make life rich and zesty.

The people around me are staring at their phones. I’m staring out the window. I’ve always enjoyed doing this; the journey itself excites me more than arriving at the destination. Perhaps because I don’t see myself as a tourist. Nope. I’m a traveler. When I travel alone, the previous ‘reality’ becomes suspended and I immerse myself in alternative existences. I travel to try on a different life, a different identity. Entering that illud tempus of Mircea Eliade, I discard masks, extract myself from the dense fabric of ties and obligations, abandon the routine, and float – as it were – through the landscape. I absorb the landscape completely and melt into it. “The window as a page,” the poet Chris Abani phrased it. The journey as a sequence of pages, a story, a book in which you immerse yourself to disappear and re-emerge: to experience something else; to be someone else or, perhaps, to be several people at once.

I am traveling through fabulous Andalusia with Garcia Lorca as my only companion. I’m reading Gypsy Ballads and their lyrics – superimposed like a surreal filter on the images that race through the window – create my own augmented reality. Augmented by the light, as well. Volumes could be written about the special quality of Andalusian light. On this late February afternoon, the weather in Málaga reminds me of a long, dry autumn. Everything is ochre. The wind blows plastic bags along the boulevards, and the neighborhoods near the airport give off an industrial vibe. Nothing very traditional around here. On many a street corner, shops carrying Asian products or the same Döner-Kebap joints that I left behind in Bavaria. Even in the city center, the small neighborhood grocery stores are run by Asian immigrants: middle-aged Indian guys, or exhausted Chinese women. The same overpriced knockoffs and kitsch souvenirs made of synthetic material vie for the customer’s attention, trying as best they can to honor local attractions: flamenco dresses, Iberian flags, magnets (roughly) depicting beaches, cathedrals, and Moorish fortresses.

The day’s first revelation: as I age, every journey brings with it the increasingly distressing feeling of being uprooted and the pronounced impression that there’s nothing new under the sun. Globalized, the cities merge into each other, forming an indistinct continuum whose local characteristics remain a much too subtle spice. A dulled-down taste that is increasingly difficult to discover and relish. Initiation journeys are rare these days, and I am beginning to doubt this can be one. But patience, as they say, is key.

The best-kept and most radiant buildings seem to be the Catholic churches and parishes. Certainly, the cathedrals. Their walls and outlines are so massive that they anchor me against my will. Málaga’s Cathedral of the Incarnation, although unfinished, looks like a fortified settlement. Its northern tower is 87 m tall, the tallest cathedral in all of Andalusia. A fortress of God unfolding impetuously not only vertically but also horizontally. Unlike German Gothic, which features slender, jagged spires resembling Alpine peaks, these cathedrals awe their onlooker into submission by way of sheer mass and gravity.

Málaga: port city, coastal town, tourist metropolis

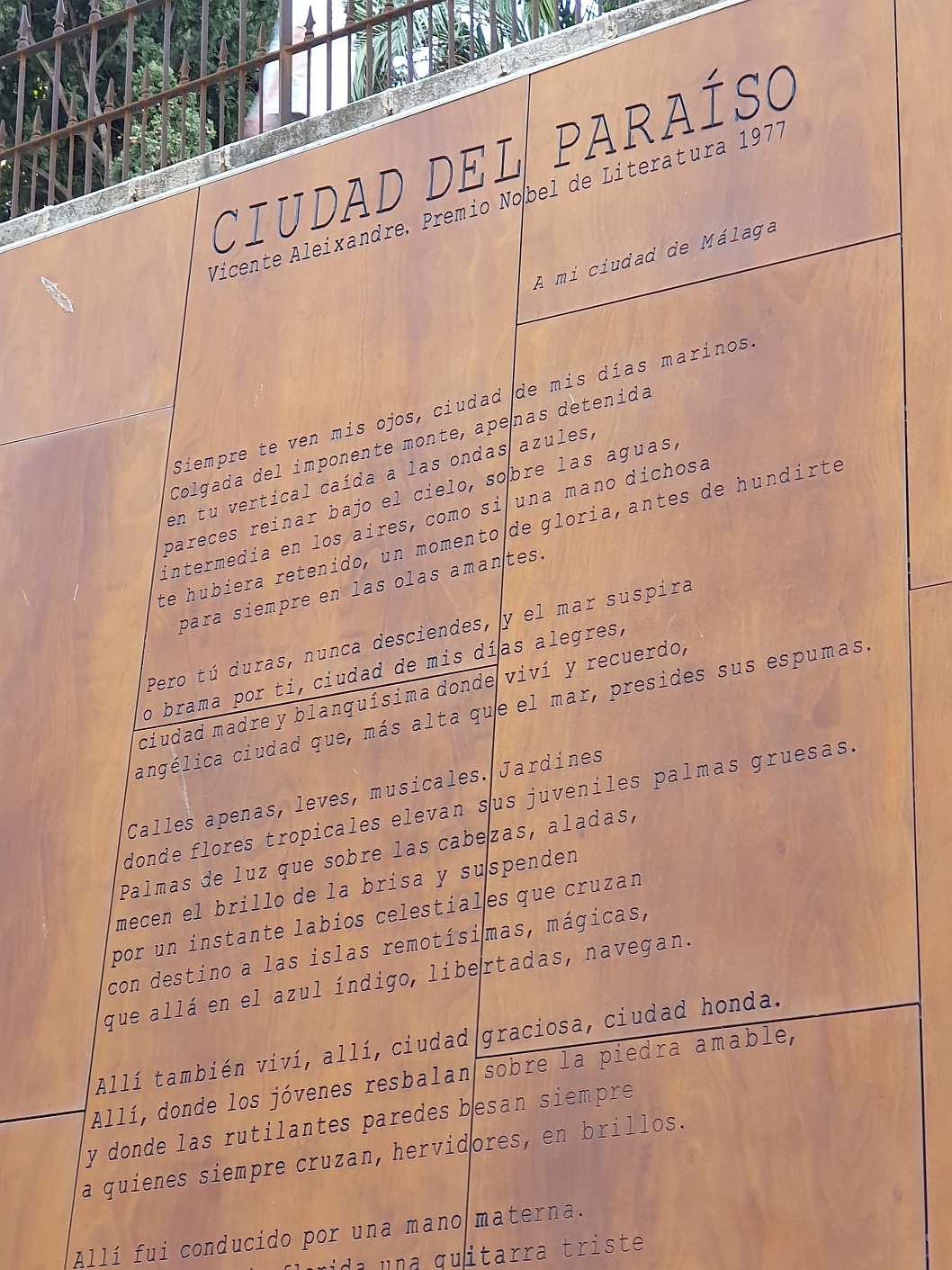

Near the coast, above the port, there is another fortress, an ancient one used for military and administrative purposes. This Arab Alcazaba is considered one of the most beautiful in all of Spain. At the base of its ramparts, there is a poem in honor of this “City of Paradise” – the words of Vicente Aleixandre, laureate of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1977. The seagulls are shrieking and the doves are cooing. Unidentifiable, shrill chirping also joins in the high-pitched cacophony of the late afternoon. The sun has already wrapped itself in evening amber. Its softening rays intensify the warm azure. I sit down briefly on the steps of the Roman theater, the only place I can still enter without a ticket at this late hour. Just opposite, on the marble slabs of the Calle Alcazabilla, a cavalcade of motorcyclists whizzes past under slender palm trees that the sea breeze is gently swaying. Above the ruins and along the cliffs, seagulls float like winged boats on the inverted sea of the sky, cradled by a crisp and unreal blue. As my steps take me inexorably toward the beach, I realize the shrill chirping belongs to the green parakeets that populate the parks.

The park and open-air theater stage by the waterfront are home to a few vagrants. These homeless people have left behind quilts and piles of clothes just as winged insects leave behind their cocoons. But, unlike butterflies, humans can’t fly away. They will return, night after night, to the same filthy, damp cocoon, and we will look away because we are on vacation; because we want to escape our own lives and feel good; because we’ve paid a lot of money for this illusion: The City of Paradise.

On the beach: a group of contorted yogis, volleyball players, some boys playing tag, two girls plucking their eyebrows, and even a daredevil swimmer in the waves, although with this rough wind that’s blowing in from the Atlantic, the temperature cannot possibly exceed 15 degrees Celsius. The sea, also yoked to the chariot of tourism and beaten down by freighters and cruise ships, stretches smoothly and hisses tiredly.

In the evening, as I stroll back to my rented studio under mother-of-pearl-colored clouds, I cannot help but wonder about the mysterious charm this shore (with its wooded hump – the Gibralfaro – and its Phoenician and Punic ruins) must have had before today’s enormous, shoe-box-shaped apartment buildings appeared along the promenade; before the glass-façades of the shops and the sea of cement around the marina. And yet, in the old town, I am fortunate enough to discover a handful of captivating places. Among them: the fin-de-siècle interior of the El Jardin restaurant, with its swinging doors and flowery tile logo on the pale pink façade; a fascinating passage, with black columns on both sides, which seems to extend endlessly in the twilight behind the Plaza de la Constitución; a musical instrument store with its beautifully aligned guitars that look like the voluptuous, naked hips of women of all colors; or the bodega where two dog owners and their quadrupeds meet around tables made of beer barrels. At nightfall, the city is filled with a special vibration; it acquires a new kind of energy. An oil-colored light pours from the street lamps, imbuing everything with an elegant and refined charm.

Day 2.

Granada, here I come!

Málaga. It’s 8 o’clock in the morning and the streets look deserted. There’s the occasional garbage truck; the occasional guy in an orange vest hosing down the pavement. Cars can be counted on the fingers of one hand. A group of cyclists, out pedaling in the crisp dawn air (middle-aged, wearing lycra), chat up a storm at the traffic lights. The old town, still asleep, extends before my eyes in all its authenticity, unvarnished.

Guadalmedina, the river that runs through this tourist metropolis (and whose name reveals its Arabic etymology), has completely dried up. In its bed of concrete, someone has drawn a soccer field in chalk. There are also skateboard ramps – an indication that this riverbed stays dry most of the time; it’s probably nothing more than a domesticated gully that catches the occasional floods from the mountains and leads them to the sea. A local gentleman walking his German shepherd argues with someone on the sidelines. As if to confirm the cliché, the words “hijo de puta” are uttered, then the conversation falls silent. On the balcony of a luxury hotel, a lady with short-cropped hair and dressed in black from head to toe (except for a blue-green scarf) is smoking. A pigeon builds a nest under a bridge with leaves in its beak. It is quiet.

Traveling to Granada by train is somewhat of a surreal experience. Since Spain was shaken by the terrible attacks at the Atocha train station, passengers have to undergo strict, airport-style security checks. We enter the deserted platform only after our luggage has passed through the scanners, and then we wait in an orderly line to board the train while the operators scan and approve our tickets one by one.

Inland, white towns lie huddled together at the foot of brownish-green mountains, surrounded by orderly orchards of orange and olive trees. Entire slopes are covered in olive trees. Lots of tunnels. There’s something Australian about the red earth.

Granada, land of my dreams…

After more than an hour, the train pulls into Granada train station. A flea market welcomes us on the outskirts of town – colorful second-hand clothes swaying in the chilly morning wind. Decorative orange trees, laden with globular fruit, line the streets and the light is blinding. The circadian rhythms of Granada’s inhabitants seem even more delayed: at 11 a.m. the men are still out for their morning jog. And these guys are every bit as chatty as the hobby cyclists of Málaga. Down in the old town, I walk past another reinforced cathedral, semicircular like an open fan, and I am getting the same sense of horizontal massiveness. Except the stone here is blackened, brownish.

The narrow streets are full of Lebanese, Iraqi, and Syrian restaurants, tastefully embedded in the urban landscape. I’m in a hurry, so I need something I can munch on the go. I settle on a spinach-and-ricotta empanada from a local bakery. Granada is also the city of Garcia Lorca (he was born not far from Santa Fé), but unfortunately, I can’t afford to stop at the museum dedicated to him. I have to make it to the main entrance of the fortress on time.

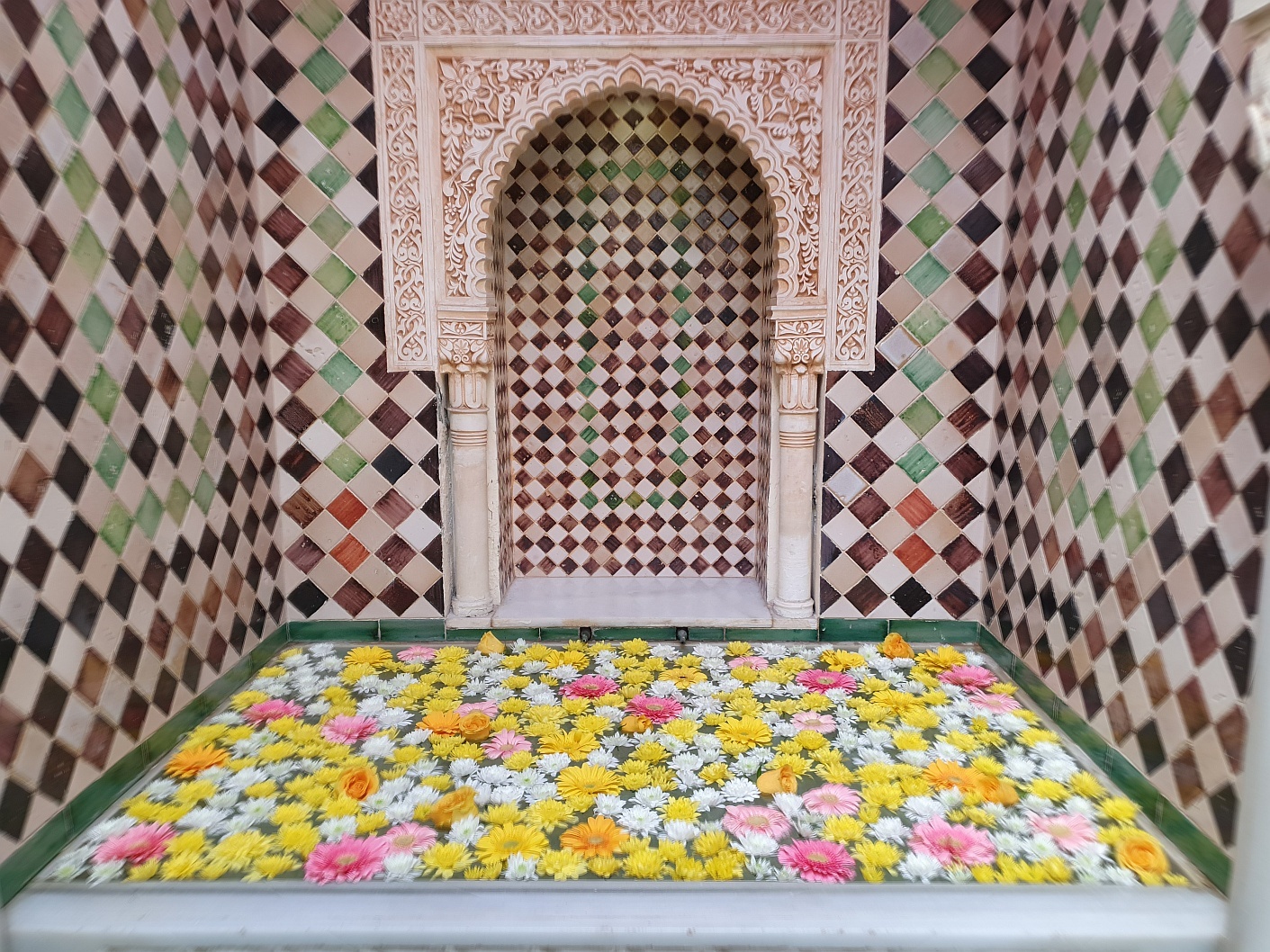

Without pre-purchased tickets, access to the Alhambra is by no means guaranteed. Today, the place has been sold out since the morning hours. The most sought-after circuits sell out months in advance. There are multiple access options; in order not to miss the Nasrid palaces, a miracle of architecture and landscaping, famous for some of the most sublime plasterwork and dazzling ceramics you’ve ever encountered, make sure that they are included in your ticket. A free audio guide can be downloaded from https://audioguia.alhambra-patronato.es/home .

All roads (and streams of tourists!) lead to Alhambra

The Alhambra sits atop a steep hill, surrounded by the rugged, barren, and snow-capped ridges of the Sierra Nevada. (Legend has it that, on a good day, you can spot Africa from the Mulhacén peak (3481 m above sea level)). I squint and make out a ski area tucked into a mountainside. Granada is a 40-minute drive away from the slopes and another 40 minutes from the beach – which means, with a bit of luck, you can experience both on the same day.

Inside the fortified city, I climb the Candle Tower. The view over the garden of the ramparts, with its fruit-bearing orange trees, palm trees, and cypresses against the cool, snow-laden backdrop of the highest mountain on the Iberian Peninsula takes my breath away.

From this vantage point, I can fully appreciate the Alcazaba, the gardens of the Saint Francis Monastery, the outline of the intimate Nasrid palaces, and the huge palace of Charles V. The courtyard of the latter, a circle made up of 32 columns, fits perfectly into the square formed by the massive outer building. The style is inspired by classical antiquity; the concept belongs to architect Pedro Machuca and was put into practice after the fortress was taken over by the Catholic monarchs (the moment when Sultan Boabdil handed over the keys remains notorious: his mother is supposed to have rebuked him with the words: ‘Don’t weep now like a woman over something you were unable to defend like a man!’). Here, too, I am humbled by the same imposing horizontality, a symbol of domination and power (the Alhambra was conquered by the Catholic monarchs in 1492.)

The contrast with the poetic sophistication and finesse of the Portico of the Partal Palace (where the Sultan of the Nasrid dynasty indulged his astronomy hobby) is striking. It is the confrontation between mass and subtlety, between the imposing Cartesian style and the discreet refinements of the enjoyment of life. The splendor of Hispano-Islamic craftsmanship of the 13th and 14th centuries enthralls me: I photograph delicate, honeycomb-shaped stuccowork and cursive or Kufic inscriptions until my phone battery runs out.

But the water management in this Palatinate city is also astonishing. Not far from the former mosque (now a church), I am fascinated by the adjacent baths (hammam), in which I almost get lost, as I would in any labyrinth. And in the Generalife, the water (so important to Muslim culture) is channeled toward the gardens, orchards, and palaces, through a complex system of aqueducts, including an elegant tiny waterway that flows down the stone balustrade of a staircase!

Moorish Gardens: mystical contemplation

Generalife (in Arabic Jannat Al-Arif ) was the summer estate that supplied fresh fruits, meats, and vegetables for the Nasrid court. It is located on the so-called “Sun Hill” next to the Alhambra. The palace – the “rural” recreational residence of the sultans who succeeded each other in Alhambra – was metaphorically called the “Royal House of Happiness”. I can imagine why. The magnificent gardens are inebriating (what is that fragrance: orange blossoms? jasmine? bougainvillea?); the battlements of the nearby defensive towers allowed – then as now – leisurely strolls in complete safety; the courtyard is intimate and full of colors (snapdragons, oxeye, tulips, roses); the fountains gurgle and murmur. Living is an art – we often forget that. Running a household, receiving guests, decorating a table, lighting a room, engaging in conversation, serving a dish – all of this is an art. Art is far superior to technique or technology. It doesn’t just change the environment, it transforms it. It is patience, ceremony. Perhaps the purpose of art is not to imitate reality, to simply capture and reproduce it, but to filter it through the humanity of the artist and thus to reinvent it.

Sensual delights, old and new

I’ve been strolling through the Alhambra for over three hours and it’s become clear to me that even three days would not be enough. Time: our eternal enemy, but also the primordial cosmic force making everything possible. And in this particular moment, I cannot help but think that one day, all of this will be gone. All of this beauty will disappear. That’s just how life is in our world. In fact, all of these splendors were designed to be perishable and ephemeral. In the Islamic school of thought that dominated that age, anything else would have been an insult to Allah, the only One endowed with the attribute of eternity.

I’m riveted. I would like nothing better than to stay; to stay here and wait for the evening and for tomorrow’s dawn and for the end of spring; wait here for the summer and autumn to pass. I’d like nothing better than to sit still and breathe and contemplate, but I have to catch the train back to Málaga. I leave the fortress full of melancholy and swim through the crowds that keep knocking on the gates of the Alhambra. On my way through the lower old town, I decide to have a pionono, a typical Granada dessert. This little madeleine-shaped sweet, with its aromatic, sticky core, comforts me and cheers me up.

Day 3.

Crafts and architecture in the former Caliphate of Córdoba

The city of Cordoba is larger and flatter than Granada. There is a London feel to the park near the train station, and almond and cherry trees are only just beginning to bloom. The boulevards are wide and spacious. It’s still chilly but the same blinding sun lights up the sky. There’s lots of greenery, too: palm trees, orange trees, huge plane trees, cypresses, Persian silk trees. Seeing tanning salons seems strange (or, rather, superfluous), but that’s how things are. It seems that doctor appointments via video call are also trending – I keep seeing ads for them everywhere I go.

Córdoba strikes me as a dynamic, intellectual city with a special cultural vocation. It is a place of contrasts. It is, simultaneously, the hometown of Maimonides, Averroes and Abulcasis, and the seat of the Second Tribunal of the Spanish Inquisition. Part of Córdoba’s historical heritage dates back to Roman times (there is a Roman temple, a mausoleum, as well as the well-known Roman bridge). Following the Arab conquest, Córdoba became the capital of the Islamic Caliphate on the Iberian Peninsula. And from March 7th to 17th, 2024, it was set to host a nationwide competition for the best hamburgers in Spain – an improbable crowning of the city’s millenary history.😊

Middle Ages and the Golden Age

If yesterday I was late, today I’m too early for the monuments (the ticket has a fixed entry time). The Mezquita (Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba) is a leisurely 20-minute walk from the train station. No problem, this will allow me to roam the Juderia (the old Jewish quarter where Sephardim once lived) within the city walls.

While there, I visit a seductive Andalusian house, so lovingly restored that I’m instantly conquered. What do I have to do to spend the rest of my life here on the patio, in the shade of the upper floor, among fleshy green plants? For me, this house embodies the ideal mix of beauty, sensuality, intimacy, pragmatism, and the subtle, spiritualized passion for life. Between paintings with excellent Arabic calligraphy and colorful embroidered cushions, I discover the replica of a 10th-century papermaking press. It was only in the 11th century AD that this technology spread from Andalusia to the rest of Western Europe.

The Mezquita

The former Umayyad mosque occupies a huge space, almost equivalent to an entire city block. There is a queue for tickets and audio guides, but these are still available. The courtyard welcomes me with orange and palm trees irrigated by the habitual Muslim water canals. During Islamic times, the water was sourced from the springs of the Sierra Morena, a whopping 33 kilometers upstream. In 1236, the Catholics defeated the Córdoba Caliphate and consecrated the mosque as a cathedral.

Its dark interior is fascinating. It resembles a forest of thin columns, a labyrinth crowned by double arches of white and red stone. The slender, tree-trunk-like columns in different colors create the illusion of a seemingly endless series of pseudo-portals through which one can pass, become lost, and find oneself again. Today the niches are occupied by frescoes or Christian votive paintings and statues of saints. The wild eclecticism creates a fantastic atmosphere: the arabesques and typically Muslim decorations (consisting of pure geometry and plant motifs) are juxtaposed with the anthropocentrism of the European Renaissance in an unlikely mix of aesthetic themes.

The history of this incredible building is also unforgettable: Around 750 AD, at the young age of 19, one of the last descendants of the Umayyad dynasty flees his native Syria to escape the Abbasid massacres. Five years later he arrives in Spain. After another year he conquers Córdoba and becomes the first Umayyad emir of Andalusia under the name of Abd Al-Rahman I. After establishing his capital here, he begins building the first mosque for the growing Muslim community. The year is 786 AD. The initial mosque, a much more modest one, was erected on the site of the former Basilica of St. Vincent the Martyr (dating back to the period of the Visigoth invasions – approx. 6th century AD), which Al-Rahman had previously bought from his Christian subjects. (Recent archaeological excavations in the basement have also uncovered Roman mosaics.) Three ambitious enlargements by his successors more than tripled the mosque’s square footage. At the height of the Moorish Caliphate, when Córdoba had reached half a million inhabitants and surpassed even Damascus and Byzantium in opulence, the mosque could accommodate over 40,000 Muslim worshipers.

Although Mecca lies southeast of here, the Mezquita’s mihrab, encrusted with gold and lapis lazuli, faces south. A mystery. The sophistication of the work is enthralling. The sun rays filter through the skylights at high noon, making the floating dust particles glow. It’s mystical; I am glued to the spot. I only budge when I’m already cold.

Strolling under orange trees

I stock up on some sunshine outside and stroll through a labyrinth of whitewashed walls. I enjoy a surprisingly cheap hamburger under an orange tree in the Plaza de Abades, next to buildings whose windows are framed by colorful tiles. The sun is burning. I get up and walk along increasingly narrow streets. I soon spot a guitar maker at work and spy on him for a while. When he looks up, I dart. Giddy with joy, I decide to head on down to the Guadalquivir – the river that crosses Córdoba on its way to Seville only to get swallowed up by the Atlantic in the Gulf of Cádiz…

Making plans for the future

Seville: I was going to visit the city tomorrow, but who knows if I’ll make it: my feet are raw with blisters. Besides, I’ve become obsessed with the idea of squeezing in a visit to Gibraltar to admire the Straits, the blurred outlines of Africa and the Atlas Mountains, surrounded by Barbary apes… Fabulous Andalusia, the victim of its own tourism success story, remains inexhaustible.